We shall fight for ever and ever and ever!

Rewi (Levi) Manga Maniapoto 1812(?)-1894

Most famous in history, folklore, film and novels for “Rewi’s Last Stand” at Orakau Pa (1864) against the Imperial troops with the declaration: “We shall fight for ever and ever and ever”.

Rewi was rangatira, warrior, guardian of the land and champion of Maori autonomy.

However, after years of resistance he finally realized that despite the treaty, Maori had lost control of their land. Resistance to loss of soverignty through the Land League, wars, the King movement, and religion (Pai Marire and Ringatu) had all failed. He became peacemaker and was buried at Kihikihi (‘cicada’) in 1894 at the foot of his government-built memorial.

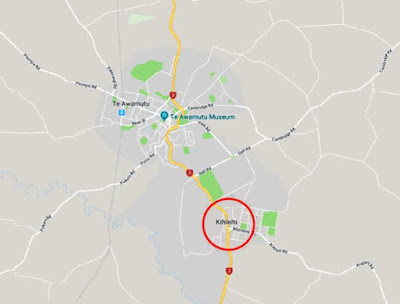

I visited Kihikihi on my 2018 winter trip to the Waikato. Fortunately it was a sunny day...

Rewi was Ngati Paretekawa, a hapu of Ngati Maniapoto, and direct descendent and namesake of his founding tribal ancestor - Maniapoto.

As a child in 1821 he accompanied his father with Te Wherowhero’s war party to Taranaki which broke the seige Te Ati Awa at Pukerangiora on the Waitara River with great slaughter from (“The Musket Wars”, R.D. Crosby P.93-99).

As a respected rangatira he was known by Maori and Pakeha for his oratory, political debate and leadership; while he was greatly influenced by missionary teaching and the agricultural practices the missions introduced.

In the 1850’s Rewi began to emerge as a prominent supporter of the King movement, raising King Te Wherowhero’s flag at Ngaruawahia when he was crowned in 1858.

Rewi, became involved in the first Taranaki War (1860-61) leading a Maniapoto war party to Waitara where they helped local iwi defeat imperial troops at Puke-ta-kauere (27 June 1860). In January 1861 Rewi led an unsuccessful attempt on General Pratt’s Number Three Redoubt at Huirangi with heavy losses (Pratt’s Sap slowly continued and the Maori stronghold of Te Arei at Pukerangiora surrendered on 19 March).

While some Kingites believed that the Treaty of Waitangi would allow Maori a degree of autonomy, Rewi disagreed - his viewpoint was widely supported among Ngati Maniapoto and Waikato. In March 1863 Rewi led the sacking government magistrate John Gorst’s office, afterwards ousting him from the Waikato. This action marked Rewi’s control over King movement politics - he proved to be a man of action while others talked and stalled.

Rewi’s fears of Governor Grey’s intentions were well-founded and all-too soon realized - war soon followed on 12 July when Grey’s army invaded the Waikato. With great energy, skill and tactical understanding Rewi led the Ngati Maniapoto resistance while the Maori forces repeatedly fell back under the relentless advance of the British, but without offering Grey and General Cameron the decisive pitched battle they sought and were determined to win.

The last brief battle in this saga was at a poorly situated, and lightly defended pa at Orakau, near Kihikihi in 1864. Rewi had advised against making a stand there, but circumstances saw him involved - leading by example against great odds. This incident, which is infamous for the gunning down of fleeing women and children by the British, is known in New Zealand folk-legend known as “Rewi’s Last Stand” - a film and a book of the battle have that title.

The stand at Orakau is also famous in folk-lore is the Maori reply to Cameron when he called upon the defenders to surrender: “Ka whawhai tonu matou, Ake! Ake! Ake!” (“We will fight on for ever and ever and ever!”)

Orakau and the war in the Waikato ended in a stalemate - Maori retreated unmolested to live in the King Country for well over a decade. Meanwhile Te Kooti and his Ringatu were active in the east of the North Island, with murderous lightening raids on settlements and a genius for evading their persuers through the Urewera. Te Kooti sought an alliance with the King movement. In a pivotal move Rewi was sent as an observer to Taupo with Te Kooti to weigh the chances of any military Ringatu success in 1869. Unfortunately for Te Kooti his ineffectual September attacks on Queenite troops there (at Tauranga-Taupo and Te Pononga) were not well-regarded by Rewi - who therefore advised the King (now Tawhiao) against joining forces with the dwindling Ringatu:

“With that...the possibility of a fighting alliance between Te Kooti and the tribes of the Waikato ended forever. And with that ended the chance that the millions of confiscated acres would be handed back. With that ended the proposal that the King Country be declared an independent state.

In this manner the pakeha hold on the North Island was secured.”

“Frontier” by Peter Maxwell p.306

Rewi was a realist as well as a warrior. At this point, with resistance futile, he therefore changed tack and began a negotiated peace settlement with the colonial government. At a meeting with Donald McLean, the native minister, in November 1869, Rewi announced that he would cease fighting. A peace settlement was concluded at Waitara on 29 June 1878 - Rewi had accepted the new order of circumstances.

Later, his loyalty to the King movement and with King Tawhiao broke in 1882 when Rewi feared that Ngati Haua would claim land which was rightfully his. His defence of his own land led to his ending his support of the King movement’s opposition to land sales, and eventually his actions in allowing the main trunk railway to enter his territory opened the way for the purchase of King Country land by the government. TheWellington-Auckland railway was completed in 1908.

For various reasons Rewi’s influence had been in decline since the late 1870’s, as he increasingly aligned with the government - which built him a large house in Kihikihi in 1880.

The impressive monument built by an appreciative colonial government honouring Rewi Maniapoto was unveiled at Kihikihi in April 1894. He died two months later aged 70-something, and after a great tangi was buried at the foot of his memorial.

Most famous in history, folklore, film and novels for “Rewi’s Last Stand” at Orakau Pa (1864) against the Imperial troops with the declaration: “We shall fight for ever and ever and ever”.

Rewi was rangatira, warrior, guardian of the land and champion of Maori autonomy.

However, after years of resistance he finally realized that despite the treaty, Maori had lost control of their land. Resistance to loss of soverignty through the Land League, wars, the King movement, and religion (Pai Marire and Ringatu) had all failed. He became peacemaker and was buried at Kihikihi (‘cicada’) in 1894 at the foot of his government-built memorial.

I visited Kihikihi on my 2018 winter trip to the Waikato. Fortunately it was a sunny day...

Rewi was Ngati Paretekawa, a hapu of Ngati Maniapoto, and direct descendent and namesake of his founding tribal ancestor - Maniapoto.

As a child in 1821 he accompanied his father with Te Wherowhero’s war party to Taranaki which broke the seige Te Ati Awa at Pukerangiora on the Waitara River with great slaughter from (“The Musket Wars”, R.D. Crosby P.93-99).

As a respected rangatira he was known by Maori and Pakeha for his oratory, political debate and leadership; while he was greatly influenced by missionary teaching and the agricultural practices the missions introduced.

In the 1850’s Rewi began to emerge as a prominent supporter of the King movement, raising King Te Wherowhero’s flag at Ngaruawahia when he was crowned in 1858.

Rewi, became involved in the first Taranaki War (1860-61) leading a Maniapoto war party to Waitara where they helped local iwi defeat imperial troops at Puke-ta-kauere (27 June 1860). In January 1861 Rewi led an unsuccessful attempt on General Pratt’s Number Three Redoubt at Huirangi with heavy losses (Pratt’s Sap slowly continued and the Maori stronghold of Te Arei at Pukerangiora surrendered on 19 March).

While some Kingites believed that the Treaty of Waitangi would allow Maori a degree of autonomy, Rewi disagreed - his viewpoint was widely supported among Ngati Maniapoto and Waikato. In March 1863 Rewi led the sacking government magistrate John Gorst’s office, afterwards ousting him from the Waikato. This action marked Rewi’s control over King movement politics - he proved to be a man of action while others talked and stalled.

Rewi’s fears of Governor Grey’s intentions were well-founded and all-too soon realized - war soon followed on 12 July when Grey’s army invaded the Waikato. With great energy, skill and tactical understanding Rewi led the Ngati Maniapoto resistance while the Maori forces repeatedly fell back under the relentless advance of the British, but without offering Grey and General Cameron the decisive pitched battle they sought and were determined to win.

The last brief battle in this saga was at a poorly situated, and lightly defended pa at Orakau, near Kihikihi in 1864. Rewi had advised against making a stand there, but circumstances saw him involved - leading by example against great odds. This incident, which is infamous for the gunning down of fleeing women and children by the British, is known in New Zealand folk-legend known as “Rewi’s Last Stand” - a film and a book of the battle have that title.

The stand at Orakau is also famous in folk-lore is the Maori reply to Cameron when he called upon the defenders to surrender: “Ka whawhai tonu matou, Ake! Ake! Ake!” (“We will fight on for ever and ever and ever!”)

Orakau and the war in the Waikato ended in a stalemate - Maori retreated unmolested to live in the King Country for well over a decade. Meanwhile Te Kooti and his Ringatu were active in the east of the North Island, with murderous lightening raids on settlements and a genius for evading their persuers through the Urewera. Te Kooti sought an alliance with the King movement. In a pivotal move Rewi was sent as an observer to Taupo with Te Kooti to weigh the chances of any military Ringatu success in 1869. Unfortunately for Te Kooti his ineffectual September attacks on Queenite troops there (at Tauranga-Taupo and Te Pononga) were not well-regarded by Rewi - who therefore advised the King (now Tawhiao) against joining forces with the dwindling Ringatu:

“With that...the possibility of a fighting alliance between Te Kooti and the tribes of the Waikato ended forever. And with that ended the chance that the millions of confiscated acres would be handed back. With that ended the proposal that the King Country be declared an independent state.

In this manner the pakeha hold on the North Island was secured.”

“Frontier” by Peter Maxwell p.306

Rewi was a realist as well as a warrior. At this point, with resistance futile, he therefore changed tack and began a negotiated peace settlement with the colonial government. At a meeting with Donald McLean, the native minister, in November 1869, Rewi announced that he would cease fighting. A peace settlement was concluded at Waitara on 29 June 1878 - Rewi had accepted the new order of circumstances.

Later, his loyalty to the King movement and with King Tawhiao broke in 1882 when Rewi feared that Ngati Haua would claim land which was rightfully his. His defence of his own land led to his ending his support of the King movement’s opposition to land sales, and eventually his actions in allowing the main trunk railway to enter his territory opened the way for the purchase of King Country land by the government. TheWellington-Auckland railway was completed in 1908.

For various reasons Rewi’s influence had been in decline since the late 1870’s, as he increasingly aligned with the government - which built him a large house in Kihikihi in 1880.

The impressive monument built by an appreciative colonial government honouring Rewi Maniapoto was unveiled at Kihikihi in April 1894. He died two months later aged 70-something, and after a great tangi was buried at the foot of his memorial.

Comments

Post a Comment